Lockout: Dublin 1913

2019 is the 106th anniversary of the 1913 lockout in Dublin. Often referred to as a strike, it is more accurate to call it a ‘lockout’ since many of those to suffer from the vengeful actions of the employers were not members of a union. In many cases, they were simply men and women who refused to sign a pledge not to join the Transport and General Workers Union or to offer any sympathetic support to the actions of that union. Such a pledge would have denied them the right to join a union of their choice that was being led by a leader they respected. All up, 20,000 workers and 80, 000 dependents were affected by the dispute.

Once regarded as the second city of the British Empire, by the early 1900s Dublin had become a bedraggled and forlorn city with crumbling buildings, high unemployment and an infant mortality rate of 27.6 per thousand, a higher toll than any city in England. A census conducted in 1911 had revealed that more than one third of families lived in one-room tenements and that the number of tenements and subletting of rooms was increasing. Lack of employment and an over-supply of unskilled labour ensured casual work at low wages was the best most working people could expect at a time when unemployment figures were constantly at around 20 per cent. With such working conditions and inadequate housing there was widespread malnutrition and infectious diseases like typhus, diphtheria and TB were at times rampant.

Into this labyrinth of slums, disease and hardship entered James Larkin, with a crusading spirit and in his own words ‘a divine mission to make men and women discontented’. Born in Liverpool of Irish parents he had commenced work on the docks at age 13 when his father had died from tuberculosis. Tall with an impressive physical appearance, Larkin was a man of tremendous energy, sheer courage and a natural and powerful orator. His activities since he had arrived in Ireland in 1907 as an organiser for the National Union of Dock Labourers had left the employers in no doubt that the Irish labour movement had acquired a new militancy and direction. First in Belfast in 1907, in Cork in 1908, in Wexford in 1911 and in Sligo in March 1913 he had led the workers to win significant improvements in wages and conditions. From one end of the country to the other Larkin gave new hope to the casual labourers in ports and workplaces around the country.

That deadline of unskilled who heaved and hauled

When the bosses called and stopped when the bosses willed.

In Dublin, Larkin was to find a fierce opponent in the person of William Martin Murphy whom Larkin sometimes described as an ‘industrial octopus’ and ‘a tramway tyrant’. He owned a chain of Irish newspapers, some hotels in the city and the Dublin Tramway Company. Larkin would find he had the power and influence to rally 400 Dublin employers to counter the demands of the workers for better pay and conditions. While Murphy claimed that he was prepared to deal with what he termed ‘respectable unions’ his record showed that long before Larkin came on the scene he was often hostile to union activists within his companies and victimisation was not unknown. He was not prepared to deal in any shape or form with a union whose mission was to change society in the interests of the working class nor was he prepared to negotiate with Larkin, whom he regarded as a revolutionary firebrand.

His objective was to eradicate the Irish Transport and General Workers Union that had been founded by Larkin in 1909 following a disagreement with the Liverpool-based NUDL. (Larkin had used union funds to support an unofficial strike of dock workers in Cork and as a result the NUDL leader, James Sexton, had taken him to court where he was found guilty of fraud and sentenced to 12 months in gaol, but released after three months).

Though his unconventional actions were frowned upon by the authorities and the English Trade Union Congress they won Larkin huge support from the rank and file workers. In Ireland over the next three years the new ITGWU went from strength to strength and despite the misgivings of the older and more conservative craft unions by 1912 it had become the most influential union in the country. With the help of his fellow socialist and syndicalist, James Connolly, the battle for the hearts and minds of working people was soon to materialise formally with the foundation of the Irish Labour Party in 1912. Both men being convinced that workers needed not only industrial muscle but political clout if real progress and change was to be won.

Murphy insisted that members of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce and the Dublin Employers Federation put pressure on their employees to leave the union. Even unions that he was prepared to tolerate were asked to expel members that took part in sympathetic strikes. He dubbed his policy ‘Murphyism’ and a direct challenge to what had become known as ‘Larkinism’ or the sympathetic strike which Larkin was using with great affect. Employers handed forms to workers to sign which read:

I hereby undertake to carry out all instructions given to me by or on behalf of my employers, and further I agree to immediately resign my membership of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. (if a member); and I further undertake that I will not join or in any way support this Union.’

By August 1913, employers in the building trades and the shipping industry were very reluctant to cross Larkin such had his power and influence grown with Dublin workers who had come to refer to their champion as ‘Big Jim.’ For the first time in history farm workers had become organised and had won a pay rise of 20 per cent when they had refused to take in the harvest. Murphy had watched these developments with growing anger and when his employees, the tramway men, demanded an increase in pay in July he dismissed out of hand all members of the union in his newspaper companies and the tramway company and let it be known that they would not be reinstated. Larkin knew that if this tactic was to succeed the ‘industrial octopus’ would win without a fight. He knew that he could not allow Murphy to have a ‘bloodless victory’. Class warrior that he was Larkin waited until the Dublin Horse Show week to hit back. There was only one answer to Murphy’s action and on August 26 at 9:45 am, on Larkin’s orders, drivers and conductors left their trams in the middle of the street and so began a struggle that would last until the middle of January 1914.

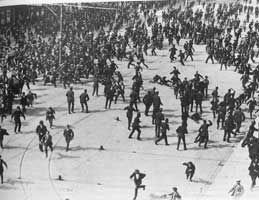

Over the next four days the city became increasingly tense and there were skirmishes that led to bloodshed and deaths. On 31 August, the government banned a meeting that Larkin was to address in the centre of the city. Larkin had been evading the police and was determined to address the meeting. Disguised as an old man, with the aid of Countess Markievicz he was smuggled into a room of the Murphy -owned Imperial Hotel and from a balcony began to address the assembled crowds.

‘I am here today,’ he roared, ‘in accordance with my promise to address you and I won't leave until I am arrested.’

That was as far as he got. The police drew batons and charged, running amok, they indiscriminately battered men and women to the ground. All down Sackville Street (O’Connell Street) the injured staggered or crawled holding their bleeding heads and faces. For the second time in a matter of days Larkin was in police custody. The press reported that in all over 400 people had been injured in the two days of rioting and that large numbers of people had been arrested. Two men, James Nolan, a thirty-three years old labourer and John Byrne, a labourer aged fifty, died from fractured skulls sustained by police batons. And later in the conflict a young woman, Alice Brady 16, a member of the IWWU was shot by a scab and died of tetanus poisoning two weeks later. A third man James Byrne, Secretary ITGWU branch Kingstown (Dunlaoire) died upon release from injuries sustained while on a hunger and thirst strike in police custody; he left a wife and six children.

Ah! Well they won and the baton and gun

Have swung where the dead men lie

By September 3, the centre of the city had become very dangerous, where civilians and police alike were very watchful of each other. In the midst of the turmoil two houses in Church Street collapsed and seven people were killed including two young children. Observers were quick to point out that many of the members of the rebellious Transport and General Workers Union inhabited houses such as those that had fallen, with the Irish Times noting that ‘the degradation of slum life’ contributed to ‘the current industrial unrest’. Later it was revealed that these tottering buildings had been ‘inspected’ just some weeks before and passed. It also became known that some members of the Dublin Corporation were the owners of such terrible tenement houses.

Over the next few months the police would carry out a process of intimidation, with raids on the homes of those believed to be among the most militant of the union members. Terrified women watched as husbands or sons were beaten or forcibly restrained while the scant furniture they still possessed was smashed to pieces. More lockouts were to follow; the Coal Merchants Association, the Builders Association and the Farmers Association all closed their gates to their workers. At Jacob's biscuit factory almost 3000 women were thrown on to the street. Members of the Irish Women Workers Union, led by Larkin’s sister Delia, they were part of the forty-five unions that rallied to support the ITGWU and were some of the last to return to work. Among them was a young woman, Rosie Hackett, who would later become prominent in the service of the workers corps, the Irish Citizen Army, which was formed to protect the people from the excesses of the Dublin Metropolitan Police. In the 1970s she received a gold medal for a lifelong contribution to trade unionism.

Hunger stalked the city. Never being used to more than a diet that barely sustained them, now the plight of those locked out became pitiful. Under the direction of Delia Larkin huge soup kitchens were set up in the union headquarters at Liberty Hall; staffed by Countess Markievicz, Maud Gonne, Dr Kathleen Lynn and other women of the upper middle class. Writers, poets and intellectuals of all hues and views felt compelled to act. When Larkin tried to have some of the unfortunate children of the strikers sent to be billeted in homes in England these were the people that volunteered to help shepherd them to the boats. The move was denounced by the Catholic hierarchy and priests and pious Catholics picketed the ships to prevent the children ‘being exported to pagan England’. From countries around the world including Australia workers donated over 150,000 pounds to the fighting fund. To its credit the TUC sent food ships and substantial financial support from England. But it stopped short of sanctioning any sympathetic industrial action that would have perhaps made a vital difference to the ITGWU.

Hunger stalked the city. Never being used to more than a diet that barely sustained them, now the plight of those locked out became pitiful. Under the direction of Delia Larkin huge soup kitchens were set up in the union headquarters at Liberty Hall; staffed by Countess Markievicz, Maud Gonne, Dr Kathleen Lynn and other women of the upper middle class. Writers, poets and intellectuals of all hues and views felt compelled to act. When Larkin tried to have some of the unfortunate children of the strikers sent to be billeted in homes in England these were the people that volunteered to help shepherd them to the boats. The move was denounced by the Catholic hierarchy and priests and pious Catholics picketed the ships to prevent the children ‘being exported to pagan England’. From countries around the world including Australia workers donated over 150,000 pounds to the fighting fund. To its credit the TUC sent food ships and substantial financial support from England. But it stopped short of sanctioning any sympathetic industrial action that would have perhaps made a vital difference to the ITGWU.

Picture above, right: 'Bloody Sunday,' O’Connell Street, August 31, 1913

Murphy was fond of reminding the hungry workers that employers could still enjoy three square meals a day and he knew that with winter coming on those that had been locked out would be starved into submission. The odds were stacked heavily against the workers, and after months of hardship and deprivation they slowly started to drift back to work. In some instances as they reported at the gates they were presented with Murphy’s paper and asked to sign away their rights. One by one most of the workers signed and on 14 January 1914 the great lockout ended.

Many of those who had been most active were placed on a blacklist and could not find work even in other cities. Not content with a witch hunt of union activists, on the outbreak of World War 1, Murphy encouraged his fellow employers to sack able-bodied men to help recruitment for the British forces. Though some employers were prepared to support him in this, most of them baulked at any suggestions of using the ‘lockout’ again in future disputes. Businesses that lacked Murphy’s resources had suffered huge losses and learned they could not afford a long drawn out fight with the Larkin inspired workers. Nevertheless those that had been blacklisted had little choice but to enlist in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and would fight alongside the Anzacs at Gallipoli, and later on the Western Front.

And starving Dublin sends its toll of Guard and Fusilier

Food for the guns that over the world have thundered murderous peals

And Dublin’s broken union men die first on Flanders’ fields.

Though the employers won the battle they did not defeat the ITGWU. The lockout exposed the shocking slums and the appalling conditions working families were forced to endure and their fight imbued in them a spirit for change. They had learned by bitter experience that ‘An injury to one is an injury to all’ and now knew well the meaning of solidarity. By 1921 the union had over 120,000 members and Larkin went on to serve as a Labour member on the Dublin Corporation (City Council) and was elected to the Dail (Irish Parliament) on three occasions. Today on O’Connell Street,

Dublin’s main thoroughfare, there stands an imposing statue of a tall man with arms upraised in a characteristic gesture of exhortation and on the plinth the words ‘Let us rise’. On the street where once their blood was spilt; ‘Big Jim’ Larkin reminds Irish workers of what can be achieved when workers stick together.

Article by J. A. O’Brien, a former building worker. His memoir “Against the Wind” is now available via Amazon.

Views: 716

Tags: Activism, Cork, Dublin, England, History of Ireland, Irish Freedom Struggle,, Labor, Liverpool

-

Comment by Joseph P McIntyre on April 9, 2014 at 6:59pm

-

My grandfather was on that "black list" and was forced to immigrate to America to survive! My great-grandfather was a blacksmith for the railroad and was never in the union and never lost his position. His boss's came to him and because he was well liked was told to get my grandfather out of the country because he would never work again in Ireland. He scraped the money together for my grandfathers passage and here I am today!

-

Heritage Partner Comment by Against The Wind on April 12, 2014 at 3:33am -

I need to mention the lines in italics in the article are from the poem The Citizen Army by Liam McGowan who also wrote a very moving poem on the execution of James Connolly. If anyone can supply information on Liam McGowan I would be very pleased to hear from them.

James O' Brien.

Comment

The Wild Geese Shop

Get your Wild Geese merch here ... shirts, hats, sweatshirts, mugs, and more at The Wild Geese Shop.

Irish Heritage Partnership

Adverts

Extend your reach with The Wild Geese Irish Heritage Partnership.

Top Content

Videos

© 2026 Created by Gerry Regan.

Powered by

![]()

Badges | Report an Issue | Privacy Policy | Terms of Service

You need to be a member of The Wild Geese to add comments!

Join The Wild Geese